Drew seminary student connects with Native American Ministries

In the summer of 2022, Drew Theological School led students on a trip to the Blackfeet Nation in Browning, Montana. I had just completed my first year as a Masters of Divinity candidate, and was excited for this opportunity. Our group stayed at the parsonage of the Rev. Calvin Hill, senior pastor of Blackfeet United Methodist Parish (BUMP). The parish consists of three churches — one in each village: Babb, Heart Butte, and Browning.

We prepared for the trip by learning the concept of cultural humility, which emphasizes the importance of self-reflection, acknowledgement of power differentials and responsible use of power. It encourages curiosity about individuals and a recognition that one cannot truly know another person or culture.

We also learned about the Doctrine of Discovery, and the devastating role that the government and Christian missionaries played in the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples within the context of European colonialism.

Rev. Calvin Hill is a Navajo Holy Man, who provided our group with an immersion experience into the life of members of the Blackfeet Nation. We were told upon arrival to “check our privilege at the gate.” We were shocked and saddened to witness the extreme poverty of this community, and to learn of the poor quality of and access to health care; the high rates of drug and alcohol addiction; high rates of domestic violence; and the inability of this community to protect its own from being kidnapped and killed.

Their language, culture and land have been stolen. They have been lied to, manipulated, ignored and forgotten. Their trauma is inherent to their identity, and it is tragically ongoing.

Ministry focused on empowering the people

Rev. Hill was the first Native American pastor for this mostly indigenous faith community. As a Holy Man, his door was always unlocked. He started his ministry simply being present and curious as to what the Blackfeet community valued most: livestock, agriculture and horses.

He built a working ranch on the parsonage property, including an equine program. Their church established a food bank and a firewood delivery ministry. All of his ministries focused on empowering the people. He taught our group to “learn the needs, meet the needs and connect over what the people value”.

Rev. Hill shared his very intentional discernment of God’s call for him. This has been difficult at times because of his own trauma history. As a child, he was taken from his family and tribe and sent to two different boarding schools. His hair was cut; he was forced to speak English; he was kept inside to “whiten” his skin; he was physically, emotionally and sexually abused by priests.

Yet, despite having experienced this severe trauma, he continues to feel called to ministry in The United Methodist Church. A large part of his ministry has been a program to educate visiting mission teams—multifaith, national and international groups—about the reality of Indigenous peoples.

Learning about trauma and healing from CONAM

Now, I will jump forward to a year later. During the EPA Annual Conference in May 2023, I had the pleasure of meeting Verna Colliver at the CONAM (Committee on Native American Ministries) display table. In our conversation, I learned that CONAM has a longtime relationship with Rev. Hill and the Blackfeet community.

The following week, I started a summer course at Drew on Indigenous Approaches to Health and Healing. Our work emphasized strength-based approaches and the concept of cultural safety, which places the responsibility on systems and providers to create a “safe space” for recipients. When working with Indigenous communities, the history of traumatic losses caused by colonization must be understood and respected to create a safe, healing environment. Safety is defined by those who receive the service.

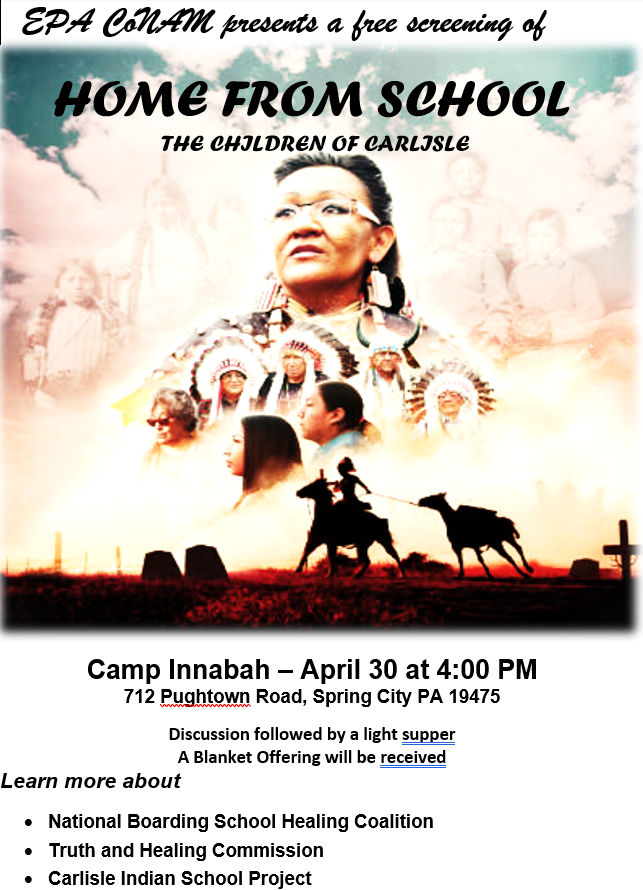

I learned that in April 2023, CONAM had hosted a screening of Home From School: the Children of Carlisle, a documentary about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Our professor welcomed the opportunity to connect, and invited members of CONAM to speak to our class about the subject. Sandi Cianciulli and Verna Colliver joined our class via Zoom, and Sandi shared a presentation about the Carlisle Indian School Project. Sandi is a descendant of the Oglala Sioux Tribe and a descendant of Carlisle Indian School students.

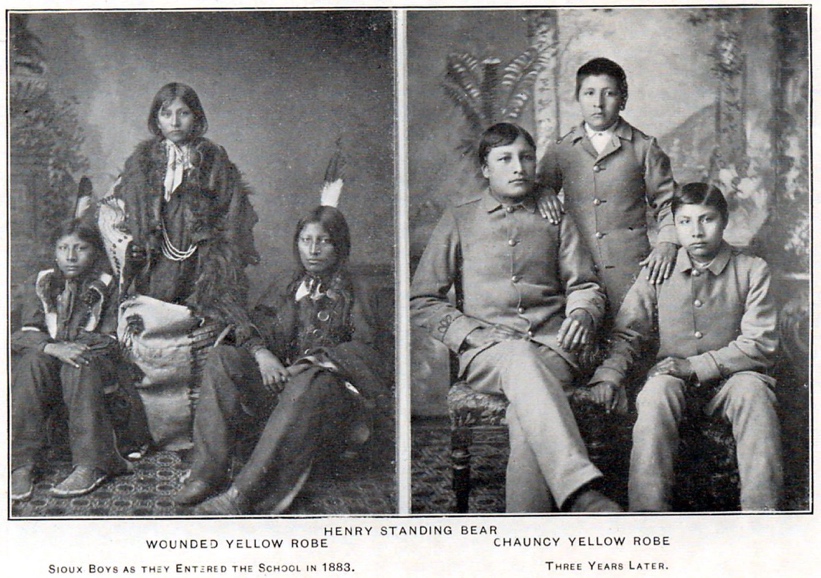

We learned that the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, located in Carlisle, PA, was the first off-reservation, government-run boarding school for American Indians. It was opened in 1879 by Lt. Col. Richard Pratt, whose personal motto was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Initially, the goal was also to control of the tribes; and so, children of Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal leaders were essentially taken hostage for this purpose.

The Carlisle School was a model for over 700 other Native American boarding schools, the majority of which were run by churches. From 7,000 to 8,000 children, representing over 140 different tribes, attended the Carlisle School during its 39 years of operation. Hundreds of children died from abuse, neglect and disease.

Forced assimilation to the dominant culture robbed individual survivors and their tribes of their customs and cultural identity. The consequences of this continue to impact Indigenous communities today.

Triumph in the midst of trauma

The history of these boarding schools is complex, however; and Sandi explained that in the midst of the trauma, there was also triumph. She cited “the resilience of the students who survived the challenges of forced assimilation with shreds of their cultures and languages to share with future generations.

“They were our greatest generation,” she told us. “They showed the colonizers what American excellence looked like on the football field, with a renowned marching band, an undefeated debate team, and creation of the first National American Indian advocacy group, the Society of American Indians. There were so many student stories of continue leadership in their tribes and in government, stories that have been hidden for too many years.”

Sandi informed us that celebrating the resilience of those students and their families is a key part of their healing from generational trauma. Today, she helps lead the Carlisle Indian School Project, whose mission is to build an interpretive center and Native American-owned hotel and conference center. Visitors will hear students’ stories and will learn about their achievements in athletics, arts, music and advocacy. Cultural rituals and events will be held on site, creating opportunities for community, connection and healing.

What an incredible opportunity it has been to be a part of this connection with CONAM, Rev. Hill and the Blackfeet Nation, and Drew Theological School. As students and emerging faith leaders, we have been overwhelmed by the trauma but inspired by the resilience of Native American tribes and nations. And like many, we are asking the question, “How can we help?”

We can start from a place of cultural humility in our learning, and then a desire to create culturally safe spaces that will allow for healing and empowerment. From there we can be inspired to action.

Actionable steps to consider for individuals and congregations:

- Support Blackfeet United Methodist Parish (BUMP) with financial donations: https://umcmission.org/advance-project/910092/

- Get involved with CONAM: https://www.epaumc.org/category/native-american/

- Visit the Carlisle Indian School: https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/page/visiting-carlisle

The Carlisle Indian School Project offers tours of the historic campus. The Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center is an ongoing project of Dickinson College that is gathering and digitizing Carlisle Indian School records from various sources all over the country. New barracks rules are limiting hours to weekends.

- Support the Carlisle Indian School Project: https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/support/

- Host an event to watch and discuss the Home from School: the Children of Carlisle documentary with others. It is now available for streaming on Vimeo. Contact Verna Colliver at vmcolliver@gmail.com to get access. A pdf file of a 24-page Discussion & Viewer Guide is also available.

Rev. Calvin Hill is currently serving as the Congregational Resource Minister (CRM) for the Wyoming District, and he is the pastor of First UMC of Newcastle, Wyoming. Prior to this assignment, he was the pastor of Blackfeet United Methodist Parish (BUMP), Browning, Montana.

Sandi Cianciulli is descended from the Oglala Sioux Tribe located in South Dakota. She is a descendent of Carlisle Indian School students, and is the President Emeritus of the Carlisle Indian School Project. She is co-chairperson of CONAM and was born and raised in the Philadelphia area.

Verna Colliver – is Secretary of CONAM. She is also a lay member to the EPA Annual Conference and an active member of Lansdale First UMC.

*Terri Leone is a psychiatric nurse practitioner and is in her third year at Drew Theological School, located in Madison, NJ. She is a lay leader at St. Luke UMC in Bryn Mawr, PA. She recently became a member of the EPA Conference CONAM.