During its opening worship service on June 16 the Eastern PA Annual Conference will become one of many United Methodist conferences to perform an Act of Repentance toward Healing Relationships with Indigenous Peoples. The Rev. Thom White Wolf Fassett, our keynote preacher, will lead the ceremony.

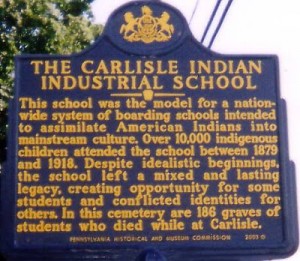

Many members may recall the uniquely moving tribute during the 2015 Annual Conference that remembered the many children buried at the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, located about a hundred miles from the Conference Office.

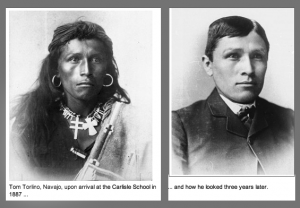

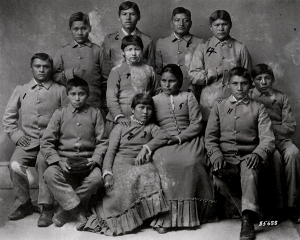

From 1879 to 1918 the former school, which today houses the U.S. Army War College, was the first of two dozen federally funded, off-reservation boarding schools that took Native American children from their tribal homes to teach and immerse them in the dominant white culture. Upon arrival, they were forbidden to speak their native languages and severely punished if they did. Their long hair was cut and they received Euro-American names and uniforms.

The goal was to rid them of every aspect of their diverse cultural and family identities so they could grow up to become acceptable and successful “Americans.” Or as Carlisle’s founder and first superintendent Captain William Pratt put it: “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

The goal was to rid them of every aspect of their diverse cultural and family identities so they could grow up to become acceptable and successful “Americans.” Or as Carlisle’s founder and first superintendent Captain William Pratt put it: “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

Of the more than 10,000 Native children from every U.S. tribe forcibly brought there from their struggling reservations out West, hundreds died, sometimes mysteriously, either at the school or soon after they were returned to their homes. Nearly 200 were buried in the school’s cemetery, which was later relocated to make way for a new entrance to the Army barracks. Careless handling of the graves and records, and mislabeling of the headstones have left many to suspect that any bones still buried there have disintegrated by now or are too fragile to be properly identified.

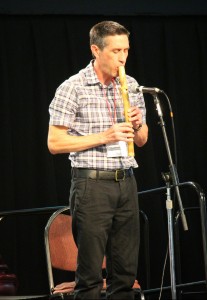

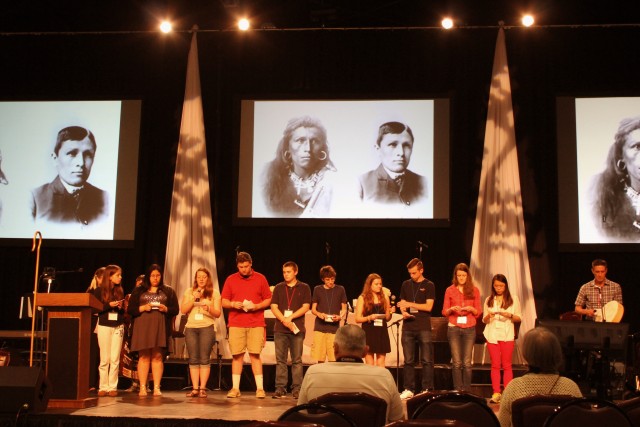

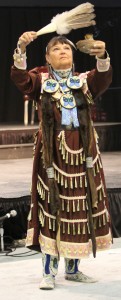

The conference’s Committee on Native American Ministries (CONAM) led last year’s solemn, 20-minute morning tribute, on May 16, to the Carlisle School’s dead and all but forgotten–“those who didn’t come home,” as the Rev. Gary Jacabella put it. They offered recollections, readings and poetry, accompanied by Native dance and flute music. Conference youth members read aloud the known Carlisle students’ names and tribes, punctuated by drumbeats, as poignant photographs of students and gravestones were displayed onscreen.

“It was so fulfilling for me to hear their names read and recognized in a Christian setting,” recalled CONAM chairperson Sandra Ciancuilli, an Oglala Sioux, during a recent CONAM meeting. “I don’t think that’s ever happened before.” She began the ceremony remembering visits to Carlisle with her father to honor their young ancestors who were among the 182 students from the Northern Plains that made up the first class at Carlisle in 1879. Like many other visitors, they would say prayers, sing songs and leave small mementos for the children at the foot of their white gravestones.

“I almost broke down when I talked about those special memories of me and my father,” she recalled. “There were people who stood up and shook my hand later, and others who clapped. I walked out of there feeling as if I was floating four feet off the ground.”

“This was very meaningful and gives us a lot to think about,” Bishop Peggy Johnson told the audience following the memorial tribute. “I encourage each of you to do some kind of remembrance and awareness training, as we prepare for our 2016 Act of Repentance.”

View recorded video of the CONAM tribute to the Carlisle School’s buried children on our Website. |

Photo by Sabrina Daluisio.

“I got the sense that we had everyone’s attention,” recalled CONAM member Verna Colliver. “They weren’t sitting there looking at their cell phones.”

But fellow member Sherry Wack said there were people “who didn’t like being upset and felt seeing the pictures and hearing the names was terrible.” Some, she added, thought last year’s Carlisle memorial was the Act of Repentance and were unhappy that there would be another ceremony this year.

“A lot of people don’t like feeling the shame and feeling responsible,” explained committee member Barbara Christy, a Seneca who recently joined First UMC Phoenixville with her husband, Barry Lee. He “blesses the ground” each year before Annual Conference begins. The two musicians have performed and taught lessons about their indigenous cultures at events around the conference, including the 2015 Laity Academy. “But it’s not about feeling responsible,” she said. “It’s about knowing what happened and not repeating mistakes of the past.”

Indeed, that has been CONAM’s goal all quadrennium. Members have offered numerous workshops–at Tools for Ministry and other events–as well as sermons, worship services, multi-media presentations and bus trips to tour the Carlisle campus—all to help prepare the way so that open hearts and informed minds would be ready to embrace this year’s Act of Repentance.

Sherry Wack taught a four-week study during Lent to help members and guests of Evansburg UMC appreciate the Act of Repentance. She used Thom Fassett’s book Giving Our Hearts Away, written for a Native American history and culture course in the UM Women’s School of Christian Mission, now known as Mission u. She also recently preached on the theme, “The Act of Repentance – Why Me?”

Sherry Wack taught a four-week study during Lent to help members and guests of Evansburg UMC appreciate the Act of Repentance. She used Thom Fassett’s book Giving Our Hearts Away, written for a Native American history and culture course in the UM Women’s School of Christian Mission, now known as Mission u. She also recently preached on the theme, “The Act of Repentance – Why Me?”

“You might think there are no Native Americans in our area,” she told her listeners, “but according to the 2010 census, there are 35,000 American Indians living in Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia, Norristown and Phoenixville.

“The land we are now sitting on was once the home of the Delaware Indian tribe,” Wack continued. “But the Eastern Woodlands tribes were eventually swindled, killed or pushed west by the ‘civilized’ Christians….

“So although we as individuals may not have sinned against the original inhabitants of this land, we here, right now, are reaping the benefits of the sins of our forefathers, while many Native Americans suffer from historical trauma in the form of poverty, depression, addiction, violence and disintegration of the family….We bear corporate guilt because of what our predecessors did. This is why we need to repent.”

You can find Wack’s entire sermon and her Lenten study on our Website, as well as links to other resources, including articles, books, photographs, worship aids, a Powerpoint presentation, the video “Stories from the Circle of Life,” and information on planning an Act of Repentance.

Moreover, several recent newspaper articles report on the desire of tribes out West to reclaim their ancestors’ remains from the Carlisle cemetery. In his March 13 Philly.com feature, “Those kids never got to go home,” Jeff Gammage reports provocatively on the Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s efforts.

Moreover, several recent newspaper articles report on the desire of tribes out West to reclaim their ancestors’ remains from the Carlisle cemetery. In his March 13 Philly.com feature, “Those kids never got to go home,” Jeff Gammage reports provocatively on the Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s efforts.

“They want the bones of their children back,” he writes. “They want the remains of the boys and girls who were taken from their American Indian families in the West, spirited a thousand miles to the East, and, when they died not long after arrival, were buried here in the fertile Pennsylvania soil.”

There are federal policies and precedents for repatriating Native remains. After initial refusals, the Army, which owns the Carlisle property, is now consulting with Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) experts to properly address several requests.

Why all the trouble for human remains that may not even be moveable? Russell Eagle Bear, the Rosebud Sioux Historic Preservation Officer, speaks of the historical trauma caused by the distant burials of their children in strange soil. “A hundred and thirty years later, this still has an impact on our youth,” he says in Gammage’s article. “We’re trying to make peace with those spirits and bring them home.”

Another recent article, “Woman seeks relative’s remains from Indian boarding school,” by Brendan Meyer, offers a profound and poignant account of Yufna Soldier Wolf, Director of the Northern Arapaho Tribal Historic Preservation Office in Riverton, Wyoming. Part of her job is to repatriate Northern Arapaho remains and artifacts back to their original lands via the NAGPRA process.

Her most personal and frustrating endeavor, charged to her by her grandfather long ago, has been to find and repatriate the remains of her great-uncle, Little Chief, who died and was buried at the Carlisle School. “Yufna is aware of all possibilities,” Meyer writes. “She knows there’s a chance they’ll never find Little Chief. But what’s important to her is the act of trying.”

Her most personal and frustrating endeavor, charged to her by her grandfather long ago, has been to find and repatriate the remains of her great-uncle, Little Chief, who died and was buried at the Carlisle School. “Yufna is aware of all possibilities,” Meyer writes. “She knows there’s a chance they’ll never find Little Chief. But what’s important to her is the act of trying.”

“It’s about the symbolism, about following this process,” she says. “It’s about healing and about showing that this agency is willing to say, ‘Hey, what we did was wrong, and we’re willing to give back an empty coffin if possible.’ Then at least we have closure.”

Indeed, acts of repentance and healing, like that which the Eastern PA Conference may experience in June, are acts of trying, of seeking to bring exposure and closure to a past that still hurts and haunts many sisters and brothers in our human family. And then such acts, when fully realized, may begin to open a redemptive path forward, one that may promise a future with hope for everyone.

By John W. Coleman

Eastern PA Conference Communications Director

Top Story photo by Paul Davis.