“This was a love story,” said the Rev. Robin Hynicka, lead pastor of Arch Street UMC in Philadelphia, celebrating the emancipation of his church’s beloved sanctuary guest after nearly a year in residence there. “It was all about how the love of God, family and community can lead to liberation.”

At 10 AM on Oct. 11, Javier Flores Garcia, a loving husband, father of three and undocumented immigrant from Mexico, took his first steps in 11 months onto the pavement outside Arch Street Church. He breathed the fresh air of freedom, accompanied by his family, attorney and friends. Greeted by supporters with hugs, handshakes and tears, and by a gaggle of media, he was finally freed from fear of arrest and deportation by the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency.

At 10 AM on Oct. 11, Javier Flores Garcia, a loving husband, father of three and undocumented immigrant from Mexico, took his first steps in 11 months onto the pavement outside Arch Street Church. He breathed the fresh air of freedom, accompanied by his family, attorney and friends. Greeted by supporters with hugs, handshakes and tears, and by a gaggle of media, he was finally freed from fear of arrest and deportation by the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency.

Flores, 40, had won his deportation case, thanks primarily to the support of Juntos, a Latino immigrant community-led organization in Philadelphia “fighting for our human rights as workers, parents, youth, and immigrants.”

“It’s completely overwhelming,” said Erika Almiron, Juntos’ executive director. “Resistance works… This is a day to celebrate freedom.”

Juntos attorney Brennan Gian-Grasso said his client had been granted “deferred action,” allowing him to live and work in the United States while awaiting approval of what is called a U visa. It covers victims of crimes who have suffered serious mental or physical injury and are willing to assist the government in prosecuting those responsible.

Flores first came to the U.S. in 1997, but was caught and deported to Mexico several times. He repeatedly returned to the U.S. illegally to reunite with his family, including his three U.S.-born children. They live in the Philadelphia area. After he was stabbed in a 2004 robbery assault in Bensalem, he aided law enforcement in catching, prosecuting and deporting his assailants.

In 2016, after 15 months in detention, he was released pending a judgment on his U visa request, filed in 2015 on the basis of the assistance he gave to law enforcement. But ICE threatened to deport him before the judgment could be rendered.

He now is in line to receive that visa, his attorney said, while his deferred action status means immigration authorities will take no action against him. Advocates say they expect him to be able to stay in this country permanently.

Flores entered Arch Street UMC to request sanctuary in early November 2016, among the first in the country to do so after the election of President Donald Trump. Trump vowed to crack down more harshly on undocumented immigrants and on so-called sanctuary cities that provide refuge for such immigrants to protect them from ICE agents.

Just last week a federal immigration sweep arrested 107 undocumented Philadelphia residents. It was the largest contingent of nearly 500 such immigrants seized during a four-day sweep targeting sanctuary cities around the country. The action ignited expected protests. But many people believe the U.S. has lost control of its southern borders and should arrest people who enter the country illegally and send them back home.

Advocates say ICE agents could have entered the church to seize Flores, who was featured on CBS-TV’s “60 Minutes” news show in May, in a segment on sanctuary cities. But the agency typically avoids entering churches and hospitals to make immigration arrests to avoid the likely negative publicity and public outcry.

“Love wins today,” Hynicka told the waiting, cheering crowd and two dozen news reporters, photographers and television camera operators that greeted his guest on Wednesday. He has grown close to Flores and his family, whom he credits, along with Juntos’ leaders, for keeping his friend strong and encouraged throughout his ordeal.

“Love wins today,” Hynicka told the waiting, cheering crowd and two dozen news reporters, photographers and television camera operators that greeted his guest on Wednesday. He has grown close to Flores and his family, whom he credits, along with Juntos’ leaders, for keeping his friend strong and encouraged throughout his ordeal.

The pastor said his church had sheltered homeless and hungry families before, but no one at risk of deportation. “This is a first for us,” he said. “It feels like we’re living our faith.”

“Today I’m finally going to be able to go home to my family,” said Flores in Spanish, after exiting the church holding the hands of his wife and children. He said his first wish was to play with his children, then find a job to support his family. “This has been a difficult journey.”

Time seemed endless in sanctuary, he said. “Every day is the same. You’re in the same place. But you have to stay focused and remember the final goal, and that was to be with my family.”

While living in a small room at Arch Street, he participated in worship and activities, and he worked hard, painting the church’s downstairs fellowship hall and hallway, the chapel, and parts of a wall mural that artistically depicts the many ways water is used throughout the Bible.

While living in a small room at Arch Street, he participated in worship and activities, and he worked hard, painting the church’s downstairs fellowship hall and hallway, the chapel, and parts of a wall mural that artistically depicts the many ways water is used throughout the Bible.

“Being here at the church opened his eyes to what a church ought to be,” said Hynicka in an interview. “He constantly saw people coming through our doors struggling with addiction and hunger and needing a place to stay.” The church operated a winter night shelter for about 30 men, among many other community outreach ministries.

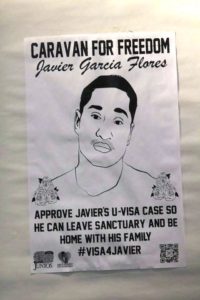

In June Hynicka and Arch Street members also joined Juntos supporters on a four-day “freedom ride,” using a van lent by Thorndale UMC, to visit the federal government’s visa processing center in Vermont, where Flores’ case was pending. They made stops at other sanctuary-supportive churches in New York and New England and hoped to raise awareness and support that might help persuade U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to grant Flores’ pending petition for legal residency. Flores tearfully bid farewell to his wife, Alma Romero, and their children as they joined the trek north on his behalf.

In June Hynicka and Arch Street members also joined Juntos supporters on a four-day “freedom ride,” using a van lent by Thorndale UMC, to visit the federal government’s visa processing center in Vermont, where Flores’ case was pending. They made stops at other sanctuary-supportive churches in New York and New England and hoped to raise awareness and support that might help persuade U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to grant Flores’ pending petition for legal residency. Flores tearfully bid farewell to his wife, Alma Romero, and their children as they joined the trek north on his behalf.

“Whenever we passed by a church steeple, Javier’s 3-years old son, Yael, would shout ‘Mi papa!’,” Hynicka recalled. “He was saying, ‘That’s where my papa is.”

CBS “60 Minutes” producer Michael Rey (left) talks with Javier Flores-García in Flores’ room at the church.

Asked if the advocacy journey may have made a difference, Hynicka said, “I believe all of what we’ve done together in faith has had an impact and led to this outcome.” He even credited Flores’ family protesting outside a detention center when he was detained there two years ago and also Roman Catholic Pope Francis’ act, during his 2016 visit to Philadelphia, of coming over during a parade to read teenage daughter Adamaris’ sign and bless her.

“This is all a powerful witness to God’s love expressed when people open their hearts and their arms to a courageous brother and his family in need,” Hynicka explained. He expects to stay in touch with the family and offer further help when needed.

“I know a lot of people don’t agree and hate me for what we’ve done. But I feel so fortunate to be in a place where we can do this, where we can see peoples’ lives changed, when they felt they had no hope otherwise.”