Church leaders repent, seek healing for sins against Native peoples

Church leaders repent, seek healing for sins against Native peoples

By John W. Coleman

The UMC’s Eastern PA Conference began its three-day annual session Thursday, June 16, with worship and a solemn ceremony that confessed and repented for an egregious legacy of mistreatment of Native Americans. The extended service and its guest preacher also challenged members to forge a future of familial bonds with indigenous Americans based on trust and accountability.

Mitakuye Oyasin (pronounced Me-tak-we O-sain)¸ a Lakota phrase meaning “All my relations,” was the term the Rev Thom White Wolf Fassett, a member of the Seneca nation, learned from his father and gifted to the conference, which met in Freedom Hall at the Lancaster County Convention Center. He emphasized the interconnectedness of all people as part of God’s creation and the mutual responsibility that truth confers on all believers.

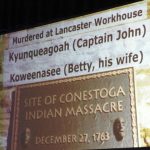

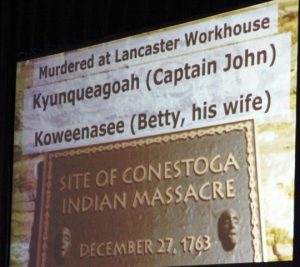

Worship leaders began their procession in front of a symbol of that interconnectedness, a vivid replica of Dean Cornwell’s 1936 painting “Treaty of Lancaster” that depicts Iroquois Federation leaders negotiating an alliance with American colonial officials in 1744. Amid Indian drum beats and chants, Barry Lee and his wife Barbara Christy, both members of First UMC Phoenixville and of the conference’s Committee on Native American Ministry (CONAM), led the procession, as they do each year, with a Friendship Dance. In their native Munsee language, they then read the names of 20 Conestoga Indians murdered in Lancaster in December 1763 by a group of white vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys

Also remembered was another atrocity: the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre of 200 defenseless Native people in Colorado–including many women and children–who were slaughtered by U.S. troops led by Col. John Chivington, a Methodist lay pastor. The UMC’s recent General Conference, meeting in Portland, Ore., received official forgiveness from tribal leaders and descendants of victims after repenting for that massacre. (Note: Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary offers a “simple definition of repent“: “To feel or show that you are sorry for something bad or wrong … and that you want to do what is right.”)

‘A New Beginning’

‘A New Beginning’

Fassett, a widely respected, international advocate for justice and reconciliation, helped conduct the Eastern PA Conference’s official Act of Repentance and Healing toward Indigenous People, along with members of the conference’s CONAM. He has done the same for other U.S. annual conferences and for the 2012 General Conference that inaugurated the Act of Repentance and Healing and called upon all annual conferences to hold similar observances by 2016.

“We have a lot of work to do together,” Fassett, a retired elder in the Upper New York Conference, told the nearly 900 clergy and lay members gathered in Lancaster. In his sermon, titled “A New Beginning,” he briefly recalled instances of the church’s historic complicity in governmental abuse of Native peoples–from treaty violations, to extermination efforts, to forced removal from their lands that led to suffering and death on the Trail of Tears, to forced assimilation of Native children at boarding schools like the first one, established in Carlisle, Pa.

He further addressed the “historical trauma” caused by that history, sadly evident in widespread alcoholism, drug abuse, poverty, violence and other ills throughout Indian Country. And he noted widespread rejection of the Christian church by Native people, whose members are often discounted and ignored by church leaders.

He further addressed the “historical trauma” caused by that history, sadly evident in widespread alcoholism, drug abuse, poverty, violence and other ills throughout Indian Country. And he noted widespread rejection of the Christian church by Native people, whose members are often discounted and ignored by church leaders.

In a Call to Repentance Sherry Wack and the Rev. Gary Jacabella, both non-Native members of CONAM, mentioned specific abuses and called on the assembly to acknowledge, apologize and repent for “the Church’s participation in the destruction of Native American peoples and their culture.” They cited the 1452 Doctrine of Discovery “wherein the Church declared war against all non-Christians throughout the world, thereby sanctioning and promoting the conquest, colonization and exploitation of non-Christian nations and their territories.”

Noting that the denomination’s 2012 General Conference repudiated that doctrine, they lamented that it is nonetheless “still used in American courts as a legal document and as a basis for human rights abuses and the seizing of Native lands.”

Shared accountability for change

Bishop Peggy Johnson, with Conference Lay Leader David Koch, led the body in a “Responsive Confession.” Members were then invited to tie gray ribbons around one another’s wrists to symbolize their shared accountability for making changes. And the bishop suggested some of those changes in a list of commitments offered on behalf of the conference. That list included:

Bishop Peggy Johnson, with Conference Lay Leader David Koch, led the body in a “Responsive Confession.” Members were then invited to tie gray ribbons around one another’s wrists to symbolize their shared accountability for making changes. And the bishop suggested some of those changes in a list of commitments offered on behalf of the conference. That list included:

- increased support of and involvement in CONAM by local churches;

- giving to the churchwide Native American Ministries Sunday offering and also to General Church Advance mission projects serving Native churches and communities;

- developing Native American leadership at all levels of the church;

- educating more non-Native people about why the Act of Repentance is important; and

- supporting United Methodist justice initiatives for Native peoples related to land and treaty rights, cultural preservation, health and education.

“We’re not here to apologize,” said Fassett, “but to seek ways to bring about healing relationships…and to reconstruct our institutions and principles so we can live together in justice.” Rather than “hand-wringing” over the horrors of history, he urged church leaders to look ahead and ask the same traditional question he once put to revered leaders of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy: “How do we prepare and make decisions that will affect the next seven generations?

“We’re not here to apologize,” said Fassett, “but to seek ways to bring about healing relationships…and to reconstruct our institutions and principles so we can live together in justice.” Rather than “hand-wringing” over the horrors of history, he urged church leaders to look ahead and ask the same traditional question he once put to revered leaders of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy: “How do we prepare and make decisions that will affect the next seven generations?

“We are kin,” Fassett said, preaching from John 1:3 and referring to a “tree of peace” throughout the earth whose roots connect all who are created by God. “Even if we leave here not having adopted one resolution, we live as kin under Jesus Christ, in whom we find oneness. I hope in the next 40 years, Native Americans can become equal partners in The United Methodist Church.”

In his ensuing evening lecture Fassett asked, “What does it mean to be a Christian claiming salvation…(and) a commitment to the teachings of our Lord Jesus Christ?”

Linking history with theology, he recalled “40 years of trying to get to this place,” through countless meetings, ceremonies, consciousness-raising dialogues and advocacy for Native American causes. “The church has not been kind to us; we have felt like step-children. But this is a moment of rebirth.”

Consecrated to new tasks

The onetime and now emeritus General Secretary of the denomination’s Board of Church and Society called for more intentional, welcoming outreach to Native Americans and other racial-ethnic peoples by United Methodists and more education about their respective histories, cultures, challenges and concerns.

“We must consecrate ourselves to new tasks,” he asserted, defining “consecrate” as “to set apart for a sacred purpose.” Describing several imaginary, diverse, typically marginalized persons struggling with life-challenges, he urged conference members to imagine inviting them into their congregations to sit among them and live and worship in community, while offering them care, dignity and friendship.

“This will be painful for many of us,” he predicted of the personal and interpersonal changes needed among disciples for the transformation of the world. “But if there’s no pain, there’s no gain.”

- Communion. Photo by John Coleman.

- Rev. Thom White Wolf Fassett. Photo by John Coleman.

- AC 2016, members singing. Photo by John Coleman.

-

Worship leaders begin the Opening Worship Procession, 2016 EPA Annual Conference. Photo by John Coleman.

- Rev. Thom White Wolf Fassett. Photo by the Rev. James Mundell.

- Members of CONAM speak at the 2016 EPA Annual Conference. Photo by Sabrina Daluisio.

- Barry Lee and his wife Barbara Christy. Photo by John Coleman.

-

Members of CONAM at the 2016 EPA Annual Conference. Photo by the Rev. James Mundell.

- Gray ribbons, to symbolize shared accountability for making changes, from the Act of Repentance Service at the 2016 EPA Annual Conference. Photo by John Coleman.

- Photo by Paul Davis.

- Top feature photo by Paul C. Davis.

- Note: LNP, Lancaster’s main daily newspaper, in its June 18 issue, covered the Eastern PA Annual Conference’s Act of Repentance and Healing service, including the Rev. Thom White Wolf Fassett’s sermon, on page 1 of its Faith & Values section. Read the article and see photos in “Act Of Repentance: United Methodist gathering focuses on past transgressions at conference” (June 17 online issue). Also see a series of color photos in the June 18 issue, titled “ United Methodist Church clergy walk to ordination at Lancaster’s First United Methodist Church” showing robed Eastern PA Conference clergy marching to First UMC Lancaster for their Service of Ordination and Commissioning. In several of the photos they are greeted by protesters.